Floating Point Representation

Learning Objectives

- Represent a real number in a floating point system

- Compute the memory requirements of storing integers versus double precision

- Define Machine Epsilon

- Identify the smallest representable floating point number

Number Systems and Bases

There are a variety of number systems in which a number can be represented. In the common base 10 (decimal) system each digit takes on one of 10 values, from 0 to 9. In base 2 (binary), each digit takes on one of 2 values, 0 or 1.

For a given \(\beta\), in the \(\beta\)-system we have:

Example:

- Decimal base:

- Binary base:

Some common bases used for numbering systems are:

- decimal: \(\beta=10\)

- binary: \(\beta=2\)

- octal: \(\beta=8\)

- hexadecimal \(\beta=16\)

Converting Integers Between Decimal and Binary

Modern computers use transistors to store data. These transistors can either be ON (1) or OFF (0). In order to store integers in a computer, we must first convert them to binary. For example, the binary representation of 23 is \((10111)_2\).

Converting an integer from binary representation (base 2) to decimal representation (base 10) is easy. Simply multiply each digit by increasing powers of 2 like so:

Converting an integer from decimal to binary is a similar process, except instead of multiplying by 2 we will be dividing by 2 and keeping track of the remainder:

Thus,

becomes \((10111)_2\) in binary.

You may find these additional resources helpful for review: Decimal to Binary 1 and Decimal to Binary 2

Converting Fractions Between Decimal and Binary

Real numbers add an extra level of complexity. Not only do they have a leading integer, they also have a fractional part. For now, we will represent a decimal number like 23.375 as \((10111.011)_2\). Of course, the actual machine representation depends on whether we are using a fixed point or a floating point representation, but we will get to that in later sections.

Converting a number with a fractional portion from binary to decimal is similar to converting to an integer, except that we continue into negative powers of 2 for the fractional part:

To convert a decimal fraction to binary, first convert the integer part to binary as previously discussed. Then, take the fractional part (ignoring the integer part) and multiply it by 2. The resulting integer part will be the binary digit. Throw away the integer part and continue the process of multiplying by 2 until the fractional part becomes 0. For example:

By combining the integer and fractional parts, we find that \(23.375 = (10111.011)_2\).

Not all fractions can be represented in binary using a finite number of digits. For example, if you try the above technique on a number like 0.1, you will find that the remaining fraction begins to repeat:

As you can see, the decimal 0.1 will be represented in binary as the infinitely repeating series \((0.00011001100110011…)_2\). The exact number of digits that get stored in a floating point number depends on whether we are using single precision or double precision.

Another resource for review: Decimal Fraction to Binary

Floating Point Numbers

The floating point representation of a binary number is similar to scientific notation for decimals. Much like you can represent 23.375 as:

you can represent \((10111.011)_2\) as:

A floating-point number can represent numbers of different orders of magnitude(very large and very small) with the same number of fixed digits.

More formally, we can define a floating point number \(x\) as:

where:

- \(\pm\) is the sign

- \(q\) is the significand

- \(m\) is the exponent

Aside from the special case of zero and subnormal numbers (discussed below), the significand is always in normalized form:

where:

- \(f\) is the fractional part of the significand

Whenever we store a normalized floating point number, the 1 is assumed. We don’t store the entire significand, just the fractional part. This is called the “hidden bit representation”, which gives one additional bit of precision.s

Properties of Normalized Floating-Point Systems

A number \(x\) in a normalized binary floating-point system has the form

- Digits: \(b_i \in {0, 1}\)

- Exponent range: Integer \(m \in [L,U]\)

- Precision: \(p = n + 1\)

- Smallest positive normalized floating-point number: \( 2^L\)

- Largest positive normalized floating-point number: \( 2^{U+1}(1-2^{-p})\)

Example

- Smallest normalized positive number:

- Largest normalized positive number:

- Any number \(x\) closer to zero than 0.0625 would underflow to zero.

- Any number \(x\) outside the range -28.0 and +28.0 would overflow to infinity.

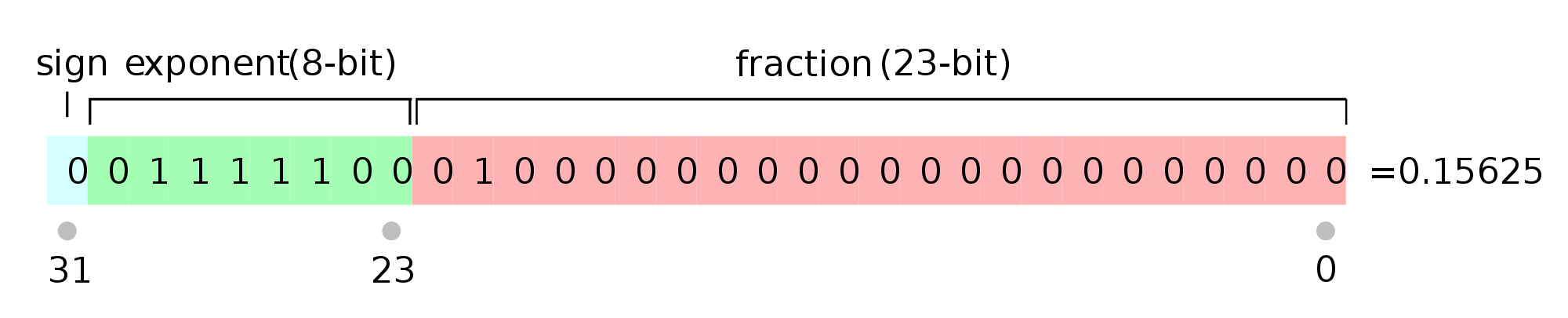

IEEE-754 Single Precision

- \(x = (-1)^s 1.f \times 2^m\)

- 1-bit sign, s = 0: positive sign, s = 1: negative sign

- 8-bit exponent \(c\), where \(c = m + 127\), we need to reserve exponent number for special cases \( c = (11111111)_2 = 255, c = (00000000)_2 = 0\), therefore \(0 < c < 255\)

- 23-bit fractional part \(f\)

- Machine epsilon: \(\epsilon = 2^{-23} \approx 1.2 \times 10^{-7}\)

- Smallest positive normalized FP number: \(UFL = 2^L = 2^{-126} \approx 1.2 \times 10^{-38}\)

- Largest positive normalized FP number: \(OFL = 2^{U+1}(1 - 2^{-p}) = 2^{128}(1 - 2^{-24}) \approx 3.4 \times 10^{38}\)

The exponent is shifted by 127 to avoid storing a negative sign. Instead of storing \(m\), we store \(c = m + 127\). Thus, the largest possible exponent is 127, and the smallest possible exponent is -126.

Example:

Convert the binary number to the normalized FP representation \(1.f \times 2^m \)

\((100101.101)_2 = (1.00101101)_2 \times 2^5\) \(s = 0,\quad f = 00101101…00,\quad m = 5\) \(c=m + 127 = 132 = (10000100)_2\)

Answer: \(0 \; 10000100 \; 00101101000000000000000\)

For additional reading about IEEE Floating Point Numbers

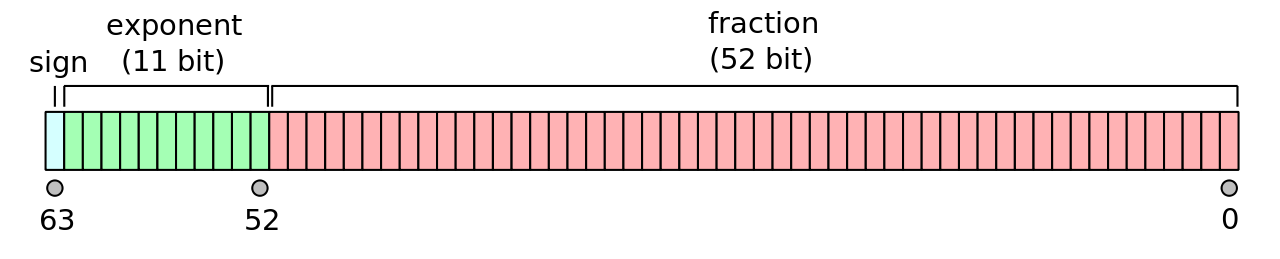

IEEE-754 Double Precision

- \(x = (-1)^s 1.f \times 2^m\)

- 1-bit sign, s = 0: positive sign, s = 1: negative sign

- 11-bit exponent \(c\), where \( c = m + 1023\), we need to reserve exponent number for special cases \( c = (11111111111)_2 = 2047, c = (00000000000)_2 = 0\), therefore \(0 < c < 2047\)

- 52-bit fractional part \(f\)

- Machine epsilon: \(\epsilon = 2^{-52} \approx 2.2 \times 10^{-16}\)

- Smallest positive normalized FP number: \(UFL = 2^L = 2^{-1022} \approx 2.2 \times 10^{-308}\)

- Largest positive normalized FP number: \(OFL = 2^{U+1}(1 - 2^{-p}) = 2^{1024}(1 - 2^{-53}) \approx 1.8 \times 10^{308}\)

The exponent is shifted by 1023 to avoid storing a negative sign. Instead of storing \(m\), we store \(c = m + 1023\). Thus, the largest possible exponent is 1023, and the smallest possible exponent is -1022.

Corner Cases in IEEE-754

There are several corner cases that arise in floating point representations.

Zero

In our definition of floating point numbers above, we said that there is always a leading 1 assumed. This is true for most floating point numbers. A notable exception is zero. In order to store zero as a floating point number, we store all zeros for the exponent and all zeros for the fractional part. Note that there can be both +0 and -0 depending on the sign bit.

Infinity

If a floating point calculation results in a number that is beyond the range of possible numbers in floating point, it is considered to be infinity. We store infinity with all ones in the exponent and all zeros in the fractional. \(+\infty\) and \(-\infty\) are distinguished by the sign bit.

NaN

Arithmetic operations that result in something that is not a number are represented in floating point with all ones in the exponent and a non-zero fractional part.

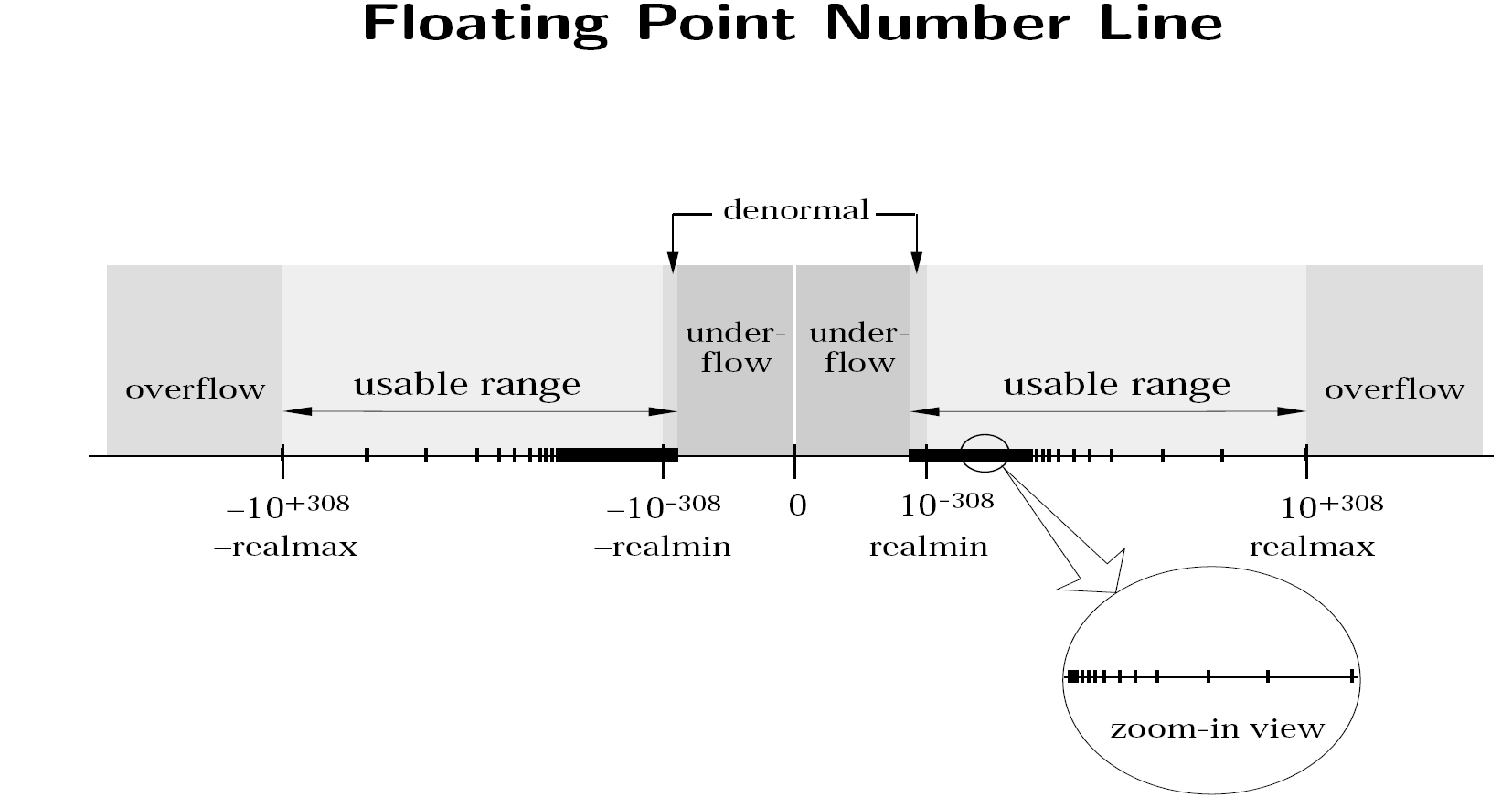

Floating Point Number Line

The above image shows the number line for the IEEE-754 floating point system.

Subnormal Numbers

A normal number is defined as a floating point number with a 1 at the start of the significand. Thus, the smallest normal number in double precision is \(1.000… \times 2^{-1022}\). The smallest representable normal number is called the underflow level, or UFL.

However, we can go even smaller than this by removing the restriction that the first number of the significand must be a 1. These numbers are known as subnormal, and are stored with all zeros in the exponent. Technically, zero is also a subnormal number.

It is important to note that subnormal numbers do not have as many significant digits as normal numbers.

IEEE-754 Single precision (32 bits):

- \( c = (00000000)_2 = 0 \)

- Exponent set to \(m\) = -126

- Smallest positive subnormal FP number: \(2^{-23} \times 2^{-126} \approx 1.4 \times 10^{-45}\)

IEEE-754 Double precision (64 bits):

- \( c = (00000000000)_2 = 0 \)

- Exponent set to \(m\) = -1022

- Smallest positive subnormal FP number: \(2^{-52} \times 2^{-1022} \approx 4.9 \times 10^{-324}\)

The use of subnormal numbers allows for more gradual underflow to zero (however subnormal numbers don’t have as many accurate bits as normalized numbers).

Machine Epsilon

Machine epsilon (\(\epsilon_m\)) is defined as the distance (gap) between \(1\) and the next largest floating point number.

For IEEE-754 single precision, \(\epsilon_m = 2^{-23}\), as shown by:

\[\epsilon_m = 1.\underbrace{000000...000}_{\text{22 bits}}{\bf 1} - 1.\underbrace{000000...000}_{\text{22 bits}}{\bf 0} = 2^{-23}\]For IEEE-754 double precision, \(\epsilon_m = 2^{-52}\), as shown by:

\[\epsilon_m = 1.\underbrace{000000...000}_{\text{51 bits}}{\bf 1} - 1.\underbrace{000000...000}_{\text{51 bits}}{\bf 0} = 2^{-52}\]Or for a general normalized floating point system \(1.f \times 2^m\), where \(f\) is represented with \(n\) bits, machine epsilon is defined as:

\[\epsilon_m = 2^{-n}\]In programming languages these values are typically available as predefined constants.

For example, in C, these constants are FLT_EPSILON and DBL_EPSILON and are defined in the float.h library.

In Python you can access these values with the code snippet below.

import numpy as np

# Single Precision

eps_single = np.finfo(np.float32).eps

print("Single precision machine eps = {}".format(eps_single))

# Double Precision

eps_double = np.finfo(np.float64).eps

print("Double precision machine eps = {}".format(eps_double))

Note: There are many definitions of machine epsilon that are used in various resources, such as the smallest number such that \(\text{fl}(1 + \epsilon_m) \ne 1\). These other definitions may give slightly different values from the definition above depending on the rounding mode (next topic). In this course, we will always use the values from the “gap” definition above.

Review Questions

- Convert a decimal number to binary.

- Convert a binary number to decimal.

- What are the differences between floating point and fixed point representation?

- Given a real number, how would you store it as a machine number?

- Given a real number, what is the rounding error involved in storing it as a machine number? What is the relative error?

- Explain the different parts of a floating-point number: sign, significand, and exponent.

- How is the exponent of a machine number actually stored?

- What is machine epsilon?

- What is underflow (UFL)?

- What is overflow?

- Why is underflow sometimes not a problem?

- Given a toy floating-point system, determine machine epsilon and UFL for that system.

- How do you store zero as a machine number?

- What are subnormal numbers?

- How are subnormal numbers represented in a machine?

- Why are subnormal numbers sometimes helpful?

- What are some drawbacks to using subnormal numbers?

ChangeLog

- 2020-04-28 Mariana Silva mfsilva@illinois.edu: moved rounding content to a separate page

- 2020-01-26 Wanjun Jiang wjiang24@illinois.edu: add normalized fp numbers, and some examples

- 2018-01-14 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: removes demo links

- 2017-12-13 Adam Stewart adamjs5@illinois.edu: fix incorrect formula under number systems and bases

- 2017-12-08 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: specifies UFL is positive

- 2017-11-19 Matthew West mwest@illinois.edu: addition of machine epsilon diagrams

- 2017-11-18 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: updates machine eps def

- 2017-11-15 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: fixes typo in converting integers

- 2017-11-14 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: clarifies when stored normalized

- 2017-11-13 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: updates machine epsilon definition, fixes inconsistent capitalization

- 2017-11-12 Erin Carrier ecarrie2@illinois.edu: minor fixes throughout, adds changelog, adds section on number systems in different bases

- 2017-11-01 Adam Stewart adamjs5@illinois.edu: first complete draft

- 2017-10-16 Luke Olson lukeo@illinois.edu: outline