Torture May Have Slowed Hunt For Bin Laden, Not Hastened It

Torture apologists are reaching precisely the wrong conclusion from the back-story of the hunt for Osama bin Laden, say experienced interrogators and intelligence professionals.

Defenders of the Bush administration’s interrogation policies have claimed vindication from reports that bin Laden was tracked down in small part due to information received from brutalized detainees some six to eight years ago.

But that sequence of events -- even if true -- doesn’t demonstrate the effectiveness of torture, these experts say. Rather, it indicates bin Laden could have been caught much earlier had those detainees been interrogated properly.

"I think that without a doubt, torture and enhanced interrogation techniques slowed down the hunt for bin Laden," said an Air Force interrogator who goes by the pseudonym Matthew Alexander and located Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the leader of al Qaeda in Iraq, in 2006.

It now appears likely that several detainees had information about a key al Qaeda courier -- information that might have led authorities directly to bin Laden years ago. But subjected to physical and psychological brutality, "they gave us the bare minimum amount of information they could get away with to get the pain to stop, or to mislead us," Alexander told The Huffington Post.

"We know that they didn’t give us everything, because they didn’t provide the real name, or the location, or somebody else who would know that information," he said.

In a 2006 study by the National Defense Intelligence College, trained interrogators found that traditional, rapport-based interviewing approaches are extremely effective with even the most hardened detainees, whereas coercion consistently builds resistance and resentment.

"Had we handled some of these sources from the beginning, I would like to think that there’s a good chance that we would have gotten this information or other information," said Steven Kleinman, a longtime military intelligence officer who has extensively researched, practiced and taught interrogation techniques.

"By making a detainee less likely to provide information, and making the information he does provide harder to evaluate, they hindered what we needed to accomplish," said Glenn L. Carle, a retired CIA officer who oversaw the interrogation of a high-level detainee in 2002.

But the discovery and killing of bin Laden was enough for defenders of the Bush administration to declare that their policies had been vindicated.

Liz Cheney, daughter of the former vice president, quickly issued a statement declaring that she was "grateful to the men and women of America’s intelligence services who, through their interrogation of high-value detainees, developed the information that apparently led us to bin Laden."

John Yoo, the lead author of the "Torture Memos," wrote in the Wall Street Journal that bin Laden's death "vindicates the Bush administration, whose intelligence architecture marked the path to bin Laden's door."

Former Bush secretary of defense Donald Rumsfeld declared that "the information that came from those individuals was critically important."

The Obama White House pushed back against that conclusion this week.

"The bottom line is this: If we had some kind of smoking-gun intelligence from waterboarding in 2003, we would have taken out Osama bin Laden in 2003," Tommy Vietor, spokesman for the National Security Council, told The New York Times.

Chronological details of the hunt for bin Laden remain murky, but piecing together various statements from administration and intelligence officials, it appears the first step may have been the CIA learning the nickname of an al Qaeda courier -- Abu Ahmed al-Kuwaiti -- from several detainees picked up after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.

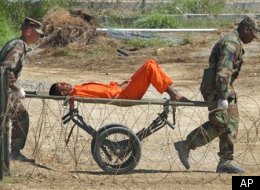

Then, in 2003, Khalid Sheikh Mohammed (KSM), the 9/11 mastermind, was captured, beaten, slammed into walls, shackled in stress positions and made to feel like he was drowning 183 times in a month. When asked about al-Kuwaiti, however, KSM denied that the he had anything to do with al Qaeda.

In 2004, officials detained a man named Hassan Ghul and brought him to one of the CIA’s black sites, where he identified al-Kuwaiti as a key courier.

A third detainee, Abu Faraj al-Libi, was arrested in 2005 and under CIA interrogation apparently denied knowing al-Kuwaiti at all.

Once the courier's real name was established -- about four years ago, and by other means -- intelligence analysts stayed on the lookout for him. After he was picked up on a monitored phone call last year, he ultimately led authorities to bin Laden.

The link between the Bush-era interrogation regime and bin Laden’s killing, then, appears tenuous -- especially since two of the three detainees in question apparently provided deceptive information about the courier even after being interrogated under durress.

"It simply strains credulity to suggest that a piece of information that may or may not have been gathered eight years ago somehow directly led to a successful mission on Sunday. That's just not the case," said White House Press Secretary Jay Carney.

But for Alexander, Kleinman and others, the key takeaway is not just that the torture didn't work, but that it was actually counterproductive.

"The question is: What else did KSM have?" Alexander asked. And he’s pretty sure he knows the answer: KSM knew the courier’s real name, "or he knew who else knew his real name, or he knew how to find him -- and he didn’t give any of that information," Alexander said.

Alexander’s book, "Kill or Capture," chronicles how the non-coercive interrogation of a dedicated al Qaeda member led to Zarqawi’s capture.

"I’m 100 percent confident that a good interrogator would have gotten additional leads" from KSM, Alexander said.

"Interrogation is all about getting access to someone’s uncorrupted memory," explained Kleinman, who as an Air Force reserve colonel in Iraq in 2003 famously tried, but failed, to stop the rampant, systemic abuse of detainees there. "And you can’t get access to someone’s uncorrupted memory by applying psychological, physical or emotional force."

Quite to the contrary, coercion is known to harden resistance. "It makes an individual hate you and find any way in their mind to fight back," and it inhibits their recall, Kleinman said. Far preferable, he said, is a "more thoughtful, culturally-enlightened, science-based approach."

"I never saw enhanced interrogation techniques work in Iraq; I never saw even harsh techniques work in Iraq," Alexander said. "In every case I saw them slow us down, and they were always counterproductive to trying to get people to cooperate."

Carle, who was not a trained interrogator, said he came to recognize that interrogation was a lot like something he did know how to do: manage intelligence assets in the field.

"Perverse and imbalanced as the relationship is between interrogator and detainee, it’s nonetheless a human relationship, and building upon that, manipulating the person, dealing straight with the person, simply coming to understand the person and vice versa, one can move forward," he told reporters on a conference call Thursday.

Carle’s upcoming book, "The Interrogator," chronicles his growing doubts about his orders from his superiors.

"The methods that I was urged to embrace, I found first-hand -- putting aside the moral and legal issues, which we really cannot put aside -- from a practical and a tactical and a strategic sense and a moral and legal one, the methods are counterproductive," he said.

"They do not work," he added. "They cause retrograde motion from what you’re seeking to accomplish. They increase resentment, not cooperation. They increase the difficulty in assessing what information you do hear is valid. They increase the likelihood that you will be given disinformation and have opposition from the person that you’re interrogating, across the board."

Carle said the detainee he worked with regressed when coerced. "All it did was increase resentment and misery," he said.

Larry Wilkerson, chief of staff under former secretary of state Colin Powell, said, "I’d be naive if I said it never worked," referring to enhanced interrogation techniques.

"Of course, occasionally it works, Wilkerson said. "But most of the time, what torture is useful for is confessions. It’s not good for getting actionable intelligence."

Experts agree that torture is particularly good at one thing: eliciting false confessions.

Bush-era interrogation techniques, were modeled after methods used by Chinese Communists to extract confessions from captured U.S. servicemen that they could then use for propaganda during the Korean War.

"Somehow our government decided that ... these were effective means of obtaining information," Carle said. "Nothing could be further from the truth."

At a hearing in Guantanamo, several years after being waterboarded, KSM described how he would lie -- specifically about bin Laden’s whereabouts -- just to make the torture stop. "I make up stories," Mohammed said. "Where is he? I don't know. Then, he torture me," KSM said of an interrogator. "Then I said, 'Yes, he is in this area.'"

There are many other reasons to be skeptical of the argument that torture can lead to actionable intelligence, and specifically that enhanced interrogation led investigators to bin Laden.

Many of the positive accomplishments once cited in defense of enhanced interrogation have since been debunked.

And though its defenders are now trying to talk up the significance of the earlier intelligence, around the time of al-Libi’s interrogation, the CIA was not stepping up the hunt for bin Laden. Instead, it was closing down the unit that had been dedicated to hunting bin Laden and his top lieutenants.

This new scenario hardly supports a defense of torture on the grounds that it’s appropriate in "ticking time bomb" scenarios, Alexander said. "Show me an interrogator who says that eight years is a good result."

The interrogation experts also noted the significant role Yoo, Rumsfeld and former Vice President Cheney each played in opening the door to controversial interrogation practices.

Wilkerson has long argued that there is ample evidence showing that "the Office of the Vice President bears responsibility for creating an environment conducive to the acts of torture and murder committed by U.S. forces in the war on terror."

Yoo wrote several memos that explicitly sanctioned measures that many have deemed constitute torture, and the memo from Rumsfeld authorizing the use of stress positions, hooding and dogs was widely seen as a sign to the troops that the "gloves could come off."

"These guys are trying to save their reputations, for one thing," Alexander said. "They have, from the beginning, been trying to prevent an investigation into war crimes."

"They don’t want to talk about the long term consequences that cost the lives of Americans," Alexander added. The way the U.S. treated its prisoners "was al-Qaeda’s number-one recruiting tool and brought in thousands of foreign fighters who killed American soldiers," Alexander said. "And who want to live with that on their conscience?"

From Bush himself on down, the defenders of his interrogation regime have long insisted that it never amounted to torture. But waterboarding, the single most controversial aspect of Bush's interrogation regime, has been an archetypal form of torture dating back to the Spanish Inquisition. It involves strapping someone to a board and simulating drowning them. The U.S. government has historically considered it a war crime.

One can quibble over the proper term for some of the other tactics employed with official sanction, including forced nudity, isolation, bombardment with noise and light, deprivation of food, forced standing, repeated beatings, applications of cold water, the use of dogs, slamming prisoners into walls, shackling them in stress positions and keeping them awake for as long as 180 hours. But they comprise violations of human dignity, as codified by the United Nations -- and championed by the U.S. government -- ever since World War II.

Many have argued that whether torture works or not is irrelevant -- that it is flatly illegal, immoral, and contrary to core American principles -- and that even if it were effective, it would still be anathema.

But that torture is unparalleled in its ability to obtain intelligence is the central argument of its defenders. To concede that torture doesn’t work -- as Alexander, Kleinman and Carle, among others, say -- would be to forfeit the whole game. It would be admitting that cruelty was both the means and the end.

And so the debate goes on.

This article has been updated to include more information on waterboarding and historical background on other interrogation techniques.

Dan Froomkin is senior Washington correspondent for The Huffington Post. You can send him an email, bookmark his page, subscribe to his RSS feed, follow him on Twitter, friend him on Facebook, and/or become a fan and get email alerts when he writes.

First Posted: 05/ 6/11 03:48 PM ET Updated: 05/ 6/11 04:55 PM ET